Notes on 3D Rarities II at the World 3D Film Expo II, 2006

By Spencer Sundell

This is an archived copy of a blog post originally published on September 24, 2006 at

URL: www.spencersundell.com/blog/2006/09/24/film_notes_on_3d_rarities_ii_at_the_world_3d_film_expo_ii_sept_17_2006/

Links within this article may have since expired, or their content changed. Original reader comments have been removed.

3-Dimension Rarities II

Sept. 17, 2006, 1pm

World 3D Film Expo II

Grauman’s Egyptian Theater

Hollywood, CA

A truly history-making screening of rare, extremely rare, and astonishingly rare 3D short films and surviving fragments, as well as excellent new 3D video footage. There were a small number of repeats of Rarities from the first (and they thought only) 3D Film Expo in 2003, but the majority of the films shown were essentially premieres.

The headline for the papers was the world premiere of the miraculously restored Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures and related test footage from 1922 — now the oldest surviving 3D film in the world, and second oldest film known to have ever been shown to a paying audience. What’s more, the 3D imaging was phenomenal, like looking into a time machine. This film is discussed further below.

The following film list, in order shown, originated from my hand-written notes made during the screening. (There were no handouts or program notes, alas.) Please pardon any rough edges.

The screening was hosted by Expo II producer Jeff Joseph and technical director Dan Symmes, who introduced each film.

3D Jamboree

1956 (USA), Technicolor polarized, widescreen

Dir. William Beaudine

Brand new dual-35mm print struck from the original negatives

Cheers erupted from the (mostly older) audience when this was announced — not just a prized rarity, but the premiere of a stunning brand new print.

3D Jamboree was made to be part of a long-running movie attraction at Disneyland that premiered on June 16, 1956 and ran at the old Fantasyland until 1964. 3D Technicolor footage of the Mousketeers was shot to wrap around Disney’s other 3D properties, the cartoons Working for Peanuts (with Donald Duck and Chip ‘n’ Dale) and Melody. This particular screening did not include the cartoons (which were both shown twice during other screenings at the Expo), but included everything featuring the Mousketeers.

The 3D had good depth and overall was pretty flawless. The color negatives had survived extremely well, and the image quality was excellent and lush. For me though, the young whippersnapper, it was just kinda too bad it was used on the Mouseketeers — although it did make for a very bizarre 1956 time capsule.

There was a singing intro (with the trademark ramrod-stiff staging required by early television), a little 3D shtick with a long balloon, and segue segments for the two cartoons. This was followed by a weird staged routine and a song sung by a very young Annette as she swings back and forth right at you in a swing and frilly 1800s sun dress. Meanwhile, the rest of the Mousketeers were arrayed in little clusters around the soundstage, dressed in period costumes and doing shtick, with a few running around doing the Keystone Kops routine. 3D shenanigans ensue, perforce.

In announcing the film to the crowd, producers Jeff and Dan unveiled, with gleeful flourish, a large poster for the film. It was one of the big cards displayed in a main entryway to Disneyland, “travel” placards to the various “lands”. The designs were only ever used there, and few (sometimes only one or two) were ever made. So this poster is most probably the only surviving copy, unless one is still lurking somewhere in the Disney archives. It looked pristine, as though it had never even been used. It had been offered on eBay, where Dan Symmes bid on it. Everyone lost when bidding didn’t meet the reserve. Coincidentally, it turned out a mutual friend knew the seller, and eventually a deal was struck and the poster was acquired for the 3D Film Archive.

Festival co-producer Dan Symmes faked us out about this film. During a breakdown on the afternoon of opening Saturday, he killed time by taking questions from the crowd and discussing 3D stuff. When someone asked about 3D Jamboree, he said they hoped to show it but one of the surviving Mousketeers, “won’t say who, wants a whole lot of money to allow it.” Either it was a puckish ruse, or they managed to work it out before the screening.

There was another later Disney 3D film attraction, Magic Journeys, that ran for some years at Disneyland’s Tomorrowland.

New Dimensions

1943, shot ca. 1942 (USA), polarized Ansco Color print

Produced by Chrysler Corporation

Color remake of In Tune with Tomorrow (1934, b/w, polarized 3D)

A portion of this film, minus the end and with new opening titles, was released in 1952 as Motor Rhythm (which was shown twice during Expo II). This screening was only of the material different from Motor Rhythm, not the fully-assembled film — namely, the original opening credits and an outro promoting Chrysler’s then-new 1941 line of cars. The omitted portion of the film is a wonderful 3D stop-motion animation sequence of a car assembling itself.

[Lumiere Anamorphic 3D Test Footage]

1934 (France), b/w polarized

The Lumiere brothers, of course, are credited with inventing the first successful film projection process in 1895. Only the truly nerdy know about the 3D experiments almost 40 years later.

The Lumiere brothers, of course, are credited with inventing the first successful film projection process in 1895. Only the truly nerdy know about the 3D experiments almost 40 years later.

The Lumiere 3D process used a rather remarkable technique that is a little difficult to explain verbally, but I will try. The two “eyes” were rotated 90 degrees and printed side-by-side in a single frame of film. A special twin-anamorphic lens compressed the roughly square aspect ratio of each “eye” of the image so that they could fit together in the alotted frame space. This is the reverse of the principle used for Cinemascope-type widescreen, where the wide image is compressed to fit into a standard 1:33 frame. Instead, the (more-or-less) 1:33 image is compressed to fit into a fraction of the frame, alongside its twin — both of them rotated so their horizon is vertical.

To restore the film, these images were extracted, unsqueezed to their true aspect ratio, and then printed to dual 35mm. This same specially-converted print was shown (and I believe premiered) at the first 3D Film Expo in 2003.

It was beautiful. Appropriately, as you can see from the anaglyphic still included here, the reel included a 3D reenactment of the Lumiere’s famous train shot from 1895. There was a little bit of artifacting at times, but it was modest and forgivable, especially since it was otherwise quite true. An anaglyphic version of this rare test footage is to be found on the Festival of 3D Movie Trailers DVD produced for the first Expo (which is still available at this writing…hint). Unfortunately, it’s still TV 3D and gives little hint of the spectacular quality of the dual-35mm print we were treated to.

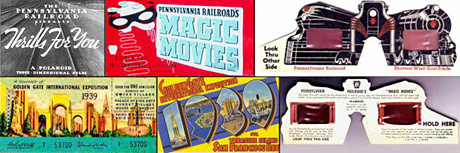

Thrills for You

1939 (USA), b/w polarized

DP: Leventhal, shooting with a Norling rig.

Produced by the Pennsylvania Railroad and originally shown at the 1939 Golden Gate Exposition in San Francisco. It had been thought lost for 65 years, until a 16mm print was recently discovered, restored, and a dual 35mm print made from that.

Excellent 3D imaging. Most of it was presented as verité documentary with music and minimal narration. Features awesome train footage — on board, passing landscapes, trainyards, factory interiors, the whole works.

[Vectograph test footage]

ca. 1953 (USA)

Joseph Mahler and Edwin H. Land

One of 2 test reels made in Los Angeles using the experimental Vectograph film stock. (Although some sources rumor of “several” reels, we were told with certainty only two were actually made). This print utilized reprinted 3D elements of the cartoon Melody (Disney, 1953). This is the only known surviving Vectograph film footage. Dr. Land (pictured at right) ordered the films destroyed, but this print, literally cut into pieces, was rescued from the trash and carefully re-assembled.

One of 2 test reels made in Los Angeles using the experimental Vectograph film stock. (Although some sources rumor of “several” reels, we were told with certainty only two were actually made). This print utilized reprinted 3D elements of the cartoon Melody (Disney, 1953). This is the only known surviving Vectograph film footage. Dr. Land (pictured at right) ordered the films destroyed, but this print, literally cut into pieces, was rescued from the trash and carefully re-assembled.

The Vectograph film stock can probably never be reproduced. Each polarized eye is printed on opposite sides of a single strip of film. Since it’s polarized, the image can be color. Although one would think this would result in shadowy or distorted image, it actually it worked surprisingly well. There was some modest though noticeable ghosting in some places (perhaps due to momentary mechanical imprecision during the optical printing), and the color had deteriorated. But overall it looked to me like a pretty successful experiment — why Dr. Land so resolutely abandoned the process is a little bit of a mystery (though it likely had to do with the 3D crash at the time).

As described by Lenny Lipton in his book, Foundations of the Stereoscopic Cinema, Land was first approached with the concept of the Vectograph in 1938 by a Czech inventor named Joseph Mahler, who made his living in part by supplying sheet polarizers.

“The Vectograph is similar to the anaglyph [red-blue] , since both images are superimposed on each other and may be projected with a standard projector without any modification. Because the coding of information depends on polarization rather than color, one would assume the full-color Vectograph might also be possible…” [Lipton, p. 88]

[William Crespinel 3D test footage]

The can the film was found in is labeled 1927, but the footage was probably actually shot ca. 1923

(USA) b/w, anaglyphic (r/b)

3D test footage shot in the early 1920s by Willliam T. Crespinel

Shown was a 1999 dual-35mm print struck from dupe neg; produced and owned by the George Eastman House, Rochester, NY (where the original still resides). Norling was apparently involved to some extent, though this was not elaborated on. These experiments were possibly related to the later Audioscopics films Pete Smith produced for MGM in the late ’30s and early ’40s.

One of only two anaglyphic films (their original format) shown during the entire festival, along with the following.

Third Dimensional Murder

(aka Murder in 3-D and Murder in Three Dimensions)

1941 (USA), b/w anaglyphic (r/b)

An original Technicolor print!

Probably the only surviving original Technicolor print of this film. The 16mm prints circulating in collectors’ circles, although generally pretty decent, are originally from a reduction dupe of (I think?) a 2nd generation print (possibly not even Technicolor).

Probably the only surviving original Technicolor print of this film. The 16mm prints circulating in collectors’ circles, although generally pretty decent, are originally from a reduction dupe of (I think?) a 2nd generation print (possibly not even Technicolor).

Overall, the effectiveness of the 3D matched that of my 16mm print, though of course this one was much clearer — and bigger!! Though the effectiveness was still uneven, the only real (tho spectacularly) bum shot was one hand-from-the-wall gimmick, which was completely misaligned. But otherwise the 3D was consistently high quality and probably the best anaglyphic 3D I’ve seen. You can read some program notes about this film I compiled a while back.

New York City in 3D

2006 (USA), color

StereoVision 3D (with Dolby polarized dual video projection)

super-wide aspect ratio (Scope-ish) — huge

A new 3D video short by SabuCat Productions. Begins with 3D views culled from the NY Public Library (stereo-opticon slides, etc.) floating about — it was very effective and wonderful to see the old views, though I found myself wanting more lingering close-ups of them. This transitioned to modern-day views of the the city, in video footage shot ca. 1996. This included flying views of the World Trade Center, which was handled with understatement, but I confess it was unexpectedly moving. We were also flown over other parts of the city, as well as given land shots.

An excellent testament to the quality possible with well-handled 3D video.

Carmenesque

1953 (USA)

Starring Lili St. Cyr

Produced and directed by Saul Lesser

Shot using the Stereo-Cine dual-35mm process by Karl Struss

A very rare dual-35mm 3D burlesque routine. Shown flat — only one eye is known to survive. According to the 3-D Film List compiled by 3-D Revolution Pictures, this was originally part of a longer project titled The 3-D Follies that was abandoned before completion.

Features a wise-cracking parrot (absolutely awful jokes) that sounds suspiciously like Mel Blanc. A real artifact of its time.

Lili St. Cyr was a burlesque star and stripper who also made a number of short films during the early and mid 1950s. The market for this sort of film had to be impossibly small — high-end gentleman’s clubs (or underworld headquarters?) that could accommodate dual-35mm projection for an adults-only audience. I’d love to know more about the production history of this film. Especially since, as I understand it, most “sexy” films during the ’50s were produced to one extent or another by the Mob.

A Day in the Country (originally Stereo-Laffs)

1953 (USA), b/w

Originally anaglyphic

Remastered to polarized dual-35mm

Produced & directed by Jack Reiger (also worked w/ Pete Smith)

Released by Lippert Pictures

One of three Lippert 3D shorts made at the time, all thought long-lost until a print of this was only recently discovered. Working from a faded and battered anaglyphic print, Dan Symmes used his 20/20 process to extract each “eye” of the red or blue image to separate motion pictures. These were then resynchronized, the image quality tuned up, and finally printed to dual 35mm for polarized interlock projection. A bumpkin family vacation, with misadventures and lots of slapstick. Shot MOS. Narrated in the Pete Smith style, complete with ham-handed sound effects. Shot somewhere around Sussex or Essex, NJ. (Dan was able to read a sign in the background from 2 frames of one shot and found the intersection on Google Maps.)

As it turns out, just weeks after Expo II concluded, Jeff Joseph unearthed paperwork that showed the film was originally titled Stereo-Laffs and had been licensed for exhibition in New York state in 1945. More recently, Joseph discovered even more amazing information: Stereo-Laffs had actually been available as early as 1941 — meaning it was probably shot in 1940!

Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures: Movies of the Future and Thru’ the Trees: Washington, DC

1922-23 (USA)

Produced & directed by William Van Doren Kelley

Photographed William T. Crespinell (some, perhaps all?)

Originally anaglyphic (r/b); fully restored and shown in a new polarized dual-35mm print

![]()

The oldest known surviving 3D footage in the world.

First shown on Dec. 24, 1922 at the Rialto Theater in New York City.

(Only screening??)

World premiere of the restored film, itself unseen since the 1920s. A landmark achievement in film preservation, especially considering the technical hurdles that had to be overcome.

The first segment was comprised of experimental footage: simple moving tableaux showing silhouetted human figures and various objects — ladders, balls being thrown and caught, some very effective stuff with poles. Shot at extremely low angle, looks like floor level. Very nice indeed.

This was then followed by excerpts from Thru’ the Trees, shot by William Crespinel in and around Washington, DC. Amazing footage, with very effective 3D — it was like stepping into a time machine. Most shots are outdoor views of various famous locations, buildings, and monuments. The camera is usually situated with intervening trees and branches, providing visual framing to enhance the depth (hence the title). Men in straw hats and Model T Fords traverse the surprisingly empty streets. My notes from the screening say simply, “Stunning.”

This is the second oldest known publicly-shown 3D footage, after The Power of Love (which played for one screening in Hollywood, at the Ambassador Hotel, and a handful more in New York City — and is still believed to be lost). ![]() For this film, Kelley used an experimental color process he had developed, called Prizma Color, which used two colors ala early Technicolor. It was used for a natural color effect during the opening “flasher” bumper, which showed the red-blue Plasticon glasses (opera style) and explained that red goes on right. The rest of the original film used Prizma to create the anaglyphic 3D effect.

For this film, Kelley used an experimental color process he had developed, called Prizma Color, which used two colors ala early Technicolor. It was used for a natural color effect during the opening “flasher” bumper, which showed the red-blue Plasticon glasses (opera style) and explained that red goes on right. The rest of the original film used Prizma to create the anaglyphic 3D effect.

The recovered original anaglyphic print was so faded that the image could barely be seen with the naked eye, and the opening “flasher” segment had faded worst of all. Nevertheless, Symmes and the lab Triage (I believe) were able to extract and recover the stereo images for this spectacular brand new b/w dual-35mm print. What’s more, they were able to successfully restore the opening bumper in its original color. Although there was a limited palette to reproduce (the glasses and a hand over a white background), it looked quite realistic — indeed, better than some of the proto-Technicolor stuff I’ve been able to see.

Rescuing this film in any viewable form would be something for the history books. That Symmes was also able to not only recreate its breathtaking 3D images and restore the Prizma Color process for future generations is an especially grand achievement. Alas, the Academy apparently failed to take note.